Reading done on January 9 2018

"Twitter and Jihad: the Communication Strategy of ISIS"

- Edited by Monica Maggioni and Paolo Magri - 2015

- ISBN 978-88-98014-67-5 (pdf edition)

- © 2015 Edizioni Epoké Firs edition: 2015

- Published by ISPI

The Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI) is an independent think tank dedicated to being a resource for government officials, business executives, journalists, civil servants, students and the public at large wishing to better understand international issues. It monitors geopolitical areas as well as major trends in international affairs.

Paolo Magri (2015), the Executive Vice-President and Director of ISPI, claims that the Islamic State “has successfully used as leverage the cultural concepts of religious Islamic tradition, so that it has become operational in the everyday life of its supporters, in future new recruits, and naturally, among its enemies” (6). He also asserts that this violent organization is waging both physical and psychological war - made of texts, images, and iconographies - on a global scale (Magri 2015, 6-7). According to Magri (2015), this book examines critically the narrative that the Islamic State portrays and deconstructs the organization’s messages, communication means and strategies, and its target audience. Magri (2015) claims that nothing in the Islamic State’s communication is left to chance and everything is carefully thought-out (8).

Notes from essays:

The Caliphate between History and Myth essay by Paolo Branca.

Branca (2015) claims that in the Muslim world the belonging to the ummah – rooted in religion – is a pan-Islamic ideal represented as an alternative to nationalism, even though the latter had brought end to the colonial occupation, it was seen as a legitimization to the territorial entities created by Western colonial powers, “splitting up what remained of the Ottoman empire according to national interests” (16-17). In his essay, Branca (2015) refers to the IS spokesperson Abu Muhammad al-Adnani al-Shami in an open letter made public at the start of the month of Ramadan in 2014 in which he announced the change of the acronym ISIS into the simple IS, the only form of state that is admissible for the believers who have not been led astray by “democracy, secularism, or nationalism”, and who are therefore invited to recognize it as their own and to side with it (19).

“On 19 September 2014 more than one-hundred-and-twenty Muslim scholars issued an ‘open letter’ addressed to the self- styled caliph, generally known by a name that in fact does not appear anywhere, You Don’t Understand Islam. This text aims to reject the arguments of al-Baghdadi’s ‘inauguration speech’ by resorting to Koran verses and prophetic quotes” (Paolo Branca 2015, 22-23)

The Centrality of the Enemy in al-Baghdadi’s Caliphate essay by Andrea Plebani, Paolo MaggioliniAccording to Plebani and Maggiolini (2015), the Islamic State proposes itself to be the ideal representation of an islamic state, and this leaves no room for compromise (29) and for the right of others to exist “in a shared social or political space, except in submission and deprivation” (27). Plebani and Maggiolini (2015) claim that this principle inspires the IS narrative of representing the enemy as humiliated and defeated (27-28).

Moreover, Plebani and Maggiolini (2015) assert that according to the Islamic Sate, the “good” Muslim living peacefully with kuffar is exposed to the most dangerous of risks of abandoning or forsaking the jihad, a major offence in the group’s eyes (35). Plebani and Maggiolini (2015) interpret the Islamic State’s view of the relationship between the believer and the non-believer as an indication of the need for Muslims to inevitably resolve this threat, first by acknowledging the risk and then by deliberately taking distance from non-believer by migrating (hijra – migration/separation) to the territories under the Islamic State’s control (35).

Plebani and Maggiolini (2015) state that the violence shown according to Hollywood standards and also inspired by video games shows that the Islamic State aims to persuade younger population for recruitment purposes; in this way, the authors assert that the Islamic State’s communication goes viral and is transmitted through a language that is easily understood by the average Western viewer, thus maximizing the psychological effect on its target (45-46).

The Islamic State: Not That Surprising, If You Know Where To Look essay by Monica Maggioni

According to Monica Maggioni (2015), the path from radicalization to recruitment, fighting and martyrdom was secret and in silence - she claims that the faces of mujaheddin were only seen after their death, when they had already turned into shahid, martyrs (53) - whereas, today, fighters hold discussions on the Internet, post videos of themselves leaving for jihad, and talk about their everyday life (53). Maggioni states that these new fighters find “a stage where they can be protagonists already in this life, before martyrdom: they already have a global audience to play for and they enjoy an unexpected popularity” (53). This “stage” is the Internet and the social media used as tools to disseminate the contemporary jihadist epic (Maggioni 2015, 55).

Through the description of the Jordanian pilot’s beheading film, Maggioni (2015) shows how the Islamic State has a remarkable quality of media output:

“The beginning is that of classic American action movies (the “Bourne” series comes to mind). the graphic and sound effects are those of a war video game. The quality of editing and image selection is truly remarkable. A 3D reconstruction of the jet flying towards Syria is shown, then flames in a village appear, then pieces of the plane and the title “Healing the believers’ chests (…)” (76).

“The extensive and careful use of graphic solutions causes us to be detached from reality and leads us to codes that we typically associate with cinema. The pilot is being skillfully depicted as the foe, someone who has allegedly perpetrated heinous crimes so despicable that the cruel fate awaiting him can only be regarded as an act of justice” (77).

“The way in which the various parts of the narration are entwined (interrogation, walk, cage) indicates that they were filmed at different moments, according to a carefully set script. Nothing is improvised: the men in uniforms, the light in the various points of the action, the symbols” (78).

Maggioni (2015) claims that the different IS videos are all coherent and consistent in terms of filming and editing methods, and all output is released on social networks in a systematic way; she states this to infer that there could be “a single director, or a small group of people, who are extremely sophisticated and familiar with editing, writing and spectacularization techniques” i.e. techniques are a combination of cinematography and video game production (78).

Through the observation of the IS’s communication choices, Maggioni claims that the caliphate’s communication methods are not random, but pursue various goals with precision and awareness.

She asserts that its first goal is to be perceived as a fully-functional state (Maggioni 2015, 80). The second goal, she claims is the proselytization within its own territory and at a global level while focusing on the message and epic tale of fighting against unjust, aggressive and corrupt West (Maggioni 2015, 80). Maggioni (2015) goes on to reveal a third level of communication goal which is aimed at other jihadist groups: with the claim that the Quran’s correct interpretation is that of the Islamic State setting up itself as a successful example of a state built on sharia law, in which rules and behaviours are based on the literary interpretation of the Quran (80).

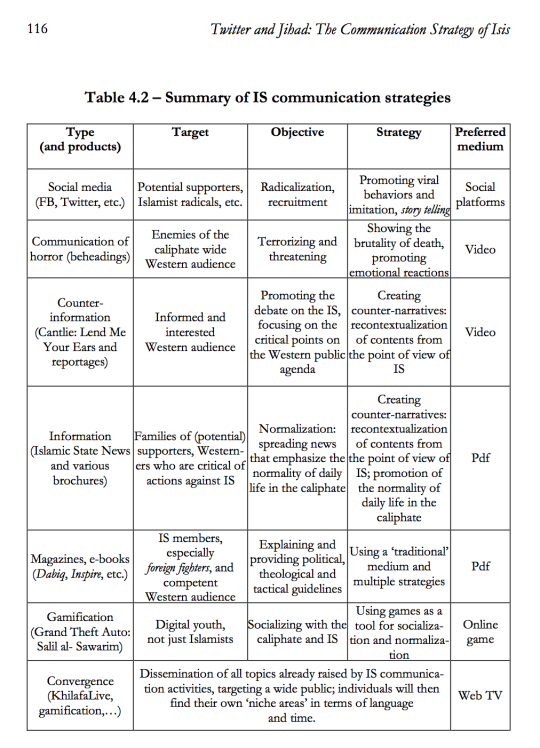

IS 2.0 and Beyond: The Caliphate’s Communication Project essay by Marco Lombardi

Marco Lombardi (2015) claims that the Islamic State uses social media as a storytelling tool through which fighters tell their experiences in the battlefield particularly those of foreign fighters (87-88).

Lombardi (2015) introduces the term gamification used in recent studies on new media:

“it expresses the idea that daily behaviours, often boring and mandatory, can be influenced and guided by a fun activity or game, which is voluntary and pleasant by nature. Somehow, gamification is a communication facilitator that helps accepting such routines” (100).

He goes on to explain the concept of convergence:

“this concept refers to the confluence on the same technological platform of traditionally different media (listening to radio, watch TV, play video games, etc. on computers and smartphones), and to the resulting ‘melting pot’ of cultural attitudes and perspectives, encouraged by this mix of genres and tools” (Lombardi 2015, 101).

Lombardi (2015) claims that the aim is to engage users for the purpose of retaining, and eventually recruiting them and guiding them towards an apparent solution of problems (101). Lombardi (2015) also states that there is much heard about game-related diseases whereby games and virtual reality overshadow real everyday life until the latter is replaced by the former, and becomes the only reference for the individual (101). The author further claims that this technique of gamification is exploited it to inform, to guide, and to provide the opportunity to experiment and to break boundaries through role games and games where the infidels are the enemy – aimed at training, recruiting and retaining, and, more importantly, at breaking the ethical barriers of life. Terrorists distribute these games on multiple platforms and even connect them with other media products, e.g. games that follow or precede videos” (Lombardi 2015, 101). Lombardi (2015) gives the example of “Grand Theft Auto: Salil al- Sawarim”, which is targeting young people, “aims at influencing the ideology of users by legitimizing terrorism and the jihad ideals while having fun” (102-103).

He also affirms that this strategy aims to achieve “the convergence of messages that are reinforced on multiple platforms, thus attracting different audiences for the same purpose: strengthening the jihad” (Lombardi 2015, 104).

“The Islamic State does not have a website of its own. Its entire network of propaganda consists of the following media types:

- Professionally edited videos. (i.e. al-Furqan, al-Hayat)

- Social media accounts (i.e. on Twitter)

- E-books and eMagazines. (i.e. Dabiq magazine)” (Lombardi 2015, 110).

Lombardi (2015) claims that the Islamic State’s online world is similar to its practical real life world; in the sense that everything is decentralized, and not having website works for its benefit -no one can hack it and claim online victory” (110). According to Lombardi (2015), the Islamic State decentralizes everything including the core leadership, this way if one province fails online or offline the Caliphate would still remain safe and can grow elsewhere (111).

Lombardi (2015) asserts that the Islamic State’s ultimate and long-term goal is to be recognized as a fully-functioning state that would control a territory, be inhabited by citizens, have institutions and infrastructure (112).

The Caliphate, Social Media and Swarms in Europe:

The Appeal of the IS Propaganda to ‘Would Be’ European Jihadists essay by Marco Arnaboldi and Lorenzo Vidino

Arnaboldi and Vidino (2015) claim that on the Internet it is possible to come across pictures showing the daily life of foreign fighters going shopping, helping people in need or reading the Quran on the battlefield (135). Even though these images seem simple and natural, the authors claim that some doctrine-related messages are included even in this type of imagery (135). Other imageries such as the mujaheddin shown with their index finger pointing upwards (the sign of the tawhid, the unicity of God), or smiling when they are dead, to show their martyrdom, also some videos showing the infliction of punishments according to the shariʿah, while others showing public bay’a ceremonies (loyalty oath to a leader) - all these aim at projecting power (Arnaboldi and Vidino 2015, 135). Moreover, on an individual level, Arnaboldi and Vidino (2015) depict two types of mujaheddin: some who boast heroism and romanticism of the humanitarian effort to save Muslims from oppression, and the others who focus on the fun that jihad offers and “its gangsterism, action and danger” (135).

“A study by CPDSI (Center for the Prevention of Sectarian Deviations of Islam) has highlighted some patterns in the influence of propaganda based on the type of content and the characteristics of the recipient. The results of this analysis show that people who suffer from anxiety and/or depression are particularly sensitive to strongly doctrinal messages, which reassure them on the uncertainty of the future by presenting a life system based on a limited set of clear values. The case of people who have grown up in excessively tolerant or atheist families is very similar: they are more prone to find comfort in messages that, contrary to their family context, impose clear doctrinal rules. As for younger subjects, many of them seem to be mainly attracted by the ‘adventurous’ side of the jihad: they believe they can live a video game experience in real life and are particularly sensitive to messages and videos of people and friends of the same age from the frontline, especially if they depict action- packed, frenzied raids. Finally, those who suffer from social exclusion or have difficulties integrating may feel strongly attracted to the promises and perspectives of a much simpler life, which would allow them to easily access elitist inclusion dynamics, invert power relations and reduce the necessary effort to live a socially fulfilling life” (Arnaboldi and Vidino 2015, 136).

The Discourse of ISIS: Messages, Propaganda and Indoctrination essay by Harith Hasan Al-Qarawee

According to Al-Qarawee (2015) the ISIS directs its messages consisting of different content, language and sophistication depending on their different target audiences, which are “the local population living under its authority, the external world – including Muslims living outside its territories – and the non-Muslims, especially Western governments and citizens” (147).

According to Al-Qarawee (2015), scenes involving children aim to give a sense of continuity for ISIS’s project, to further normalize the idea of Jihad and to show its “success” in shaping societies and building a new generation of warriors” (157).

Al-Qarawee (2015) claims that through the Caliphate, which was lost for a long time, ISIS presents itself as the paramount objective of any true Muslim to help bring back - thanks to the ISIS Mujaheddin (religious militants) - this integral part of Islam and urges Muslims to immigrate to its land, to join forces under its umbrella and support its goal of creating the ‘Islamic State’ “in every possible way” believing that every person plays a role to serve the umma and be awarded for his service (157-158).

Furthermore, according to Al-Qarawee (2015), the use of extreme violence aims at not only terrorizing ISIS’s enemies but also to attract youngster who are marginalized in society (160).